Malakand Rising 1897

The tribal attack on the Malakand frontier station on the North-West Frontier of India between 26th July and 22nd August 1897; marking the beginning of the uprisings along the frontier and described by Winston Churchill in his book ‘The Malakand Field Force’

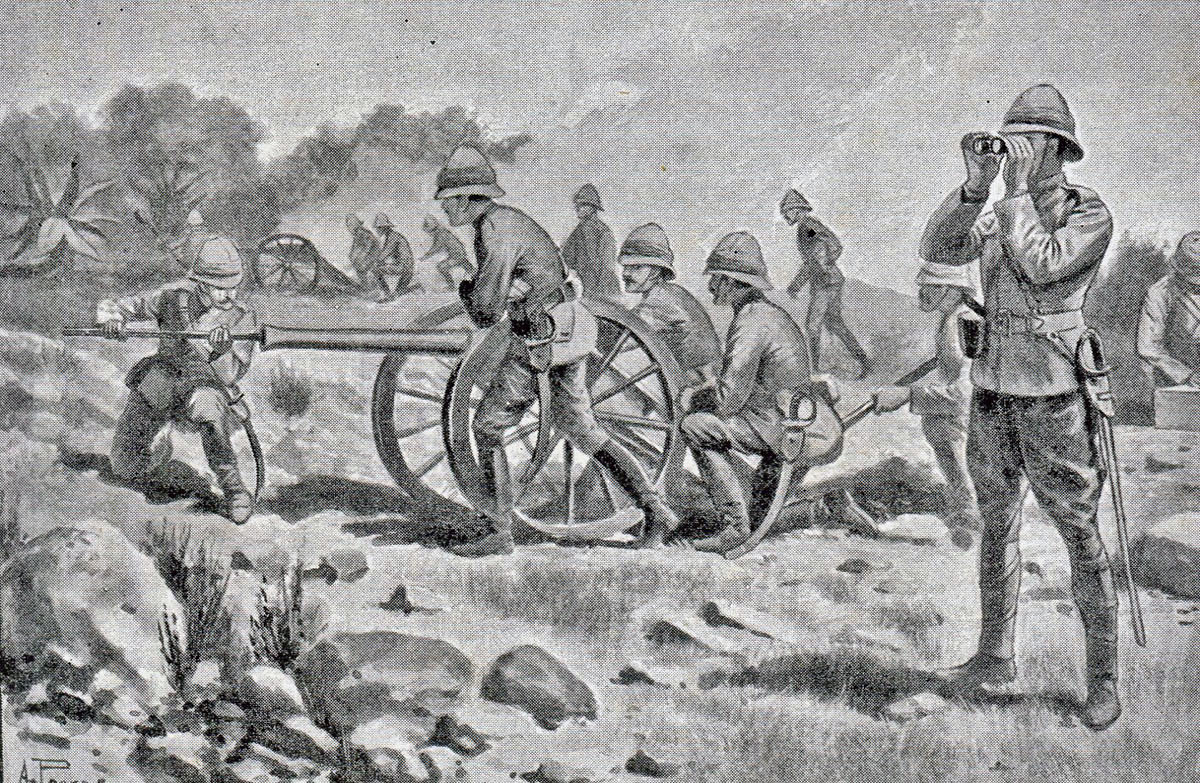

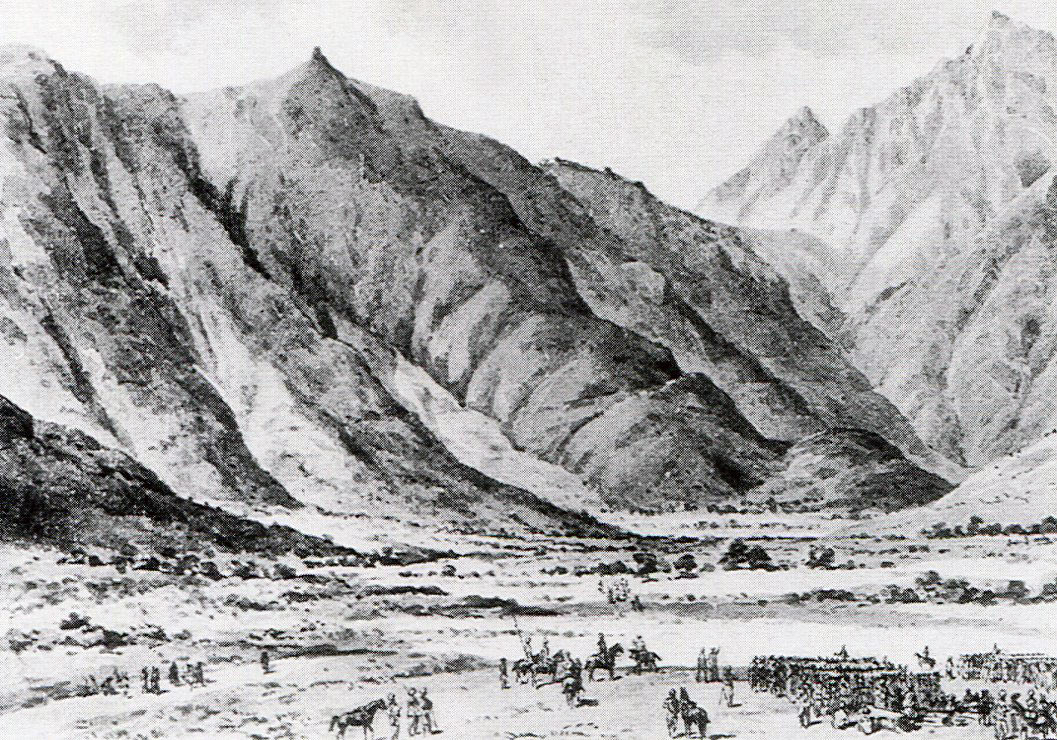

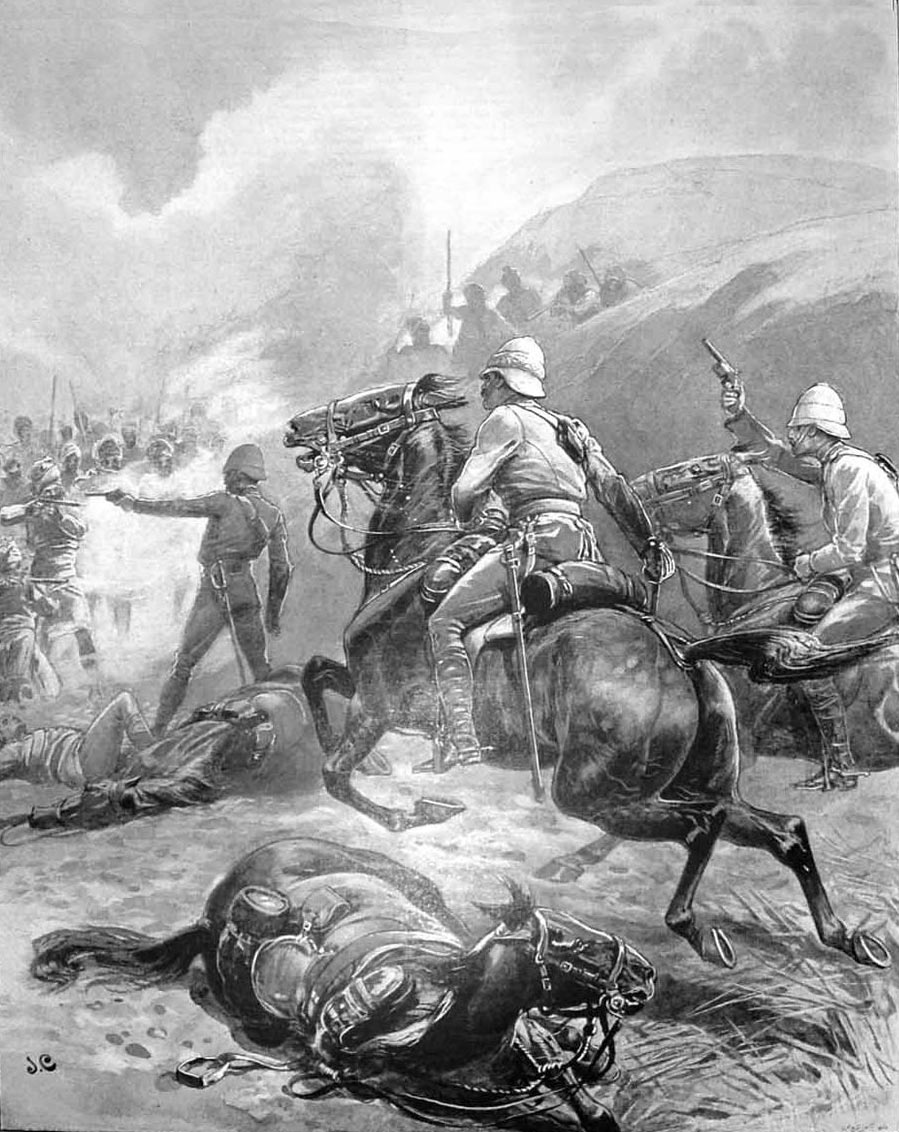

Royal Artillery advancing to Malakand: Malakand Rising, 26th July to 22nd August 1897 on the North-West Frontier of India

The previous battle of the North-West Frontier of India is the Siege and Relief of Chitral

The next battle in the British Battles sequence is the Malakand Field Force 1897:

To the North-West Frontier of India index

War: North-West Frontier of India.

Dates of the Malakand Rising: 26th July 1897 to 22nd August 1897.

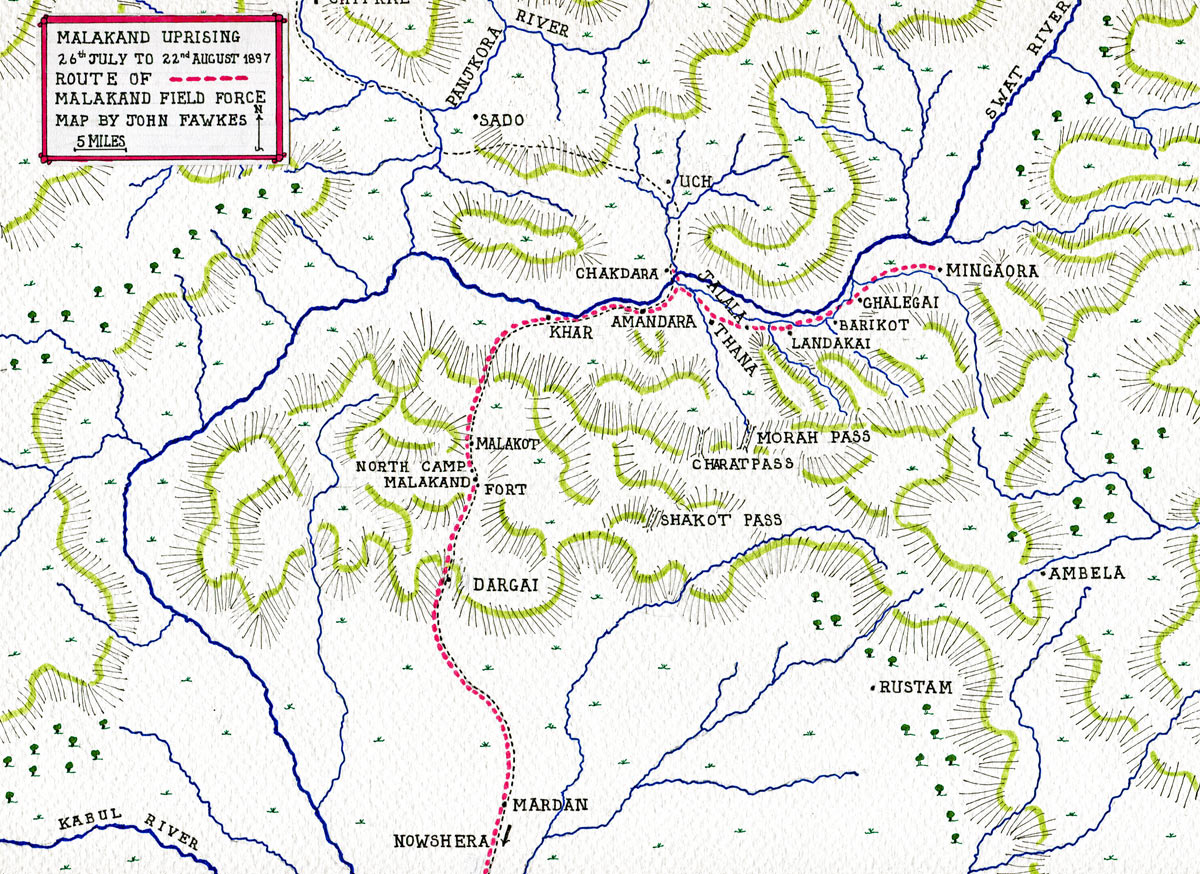

Place of the Malakand Rising: The area from the Malakand Pass on the north-west border of British India to the Swat Valley, to the north of the Malakand Pass (all now in the North-West Frontier Province of Pakistan).

Combatants in the Malakand Rising: British and Indian troops against the Pathan tribes of Swat, Bajaur and Buner (Utman Khel, Khawazazai, Baizai, Nikbi Khel, Khadakzai, Dusha Khel and others).

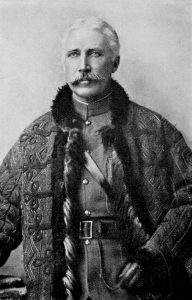

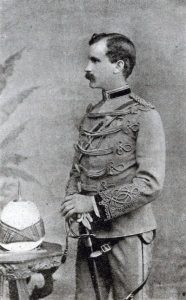

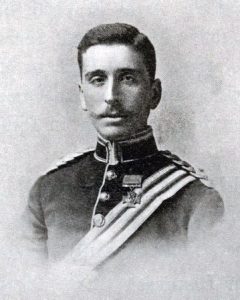

Colonel William Meiklejohn, commanding the Malakand Camp: Malakand Rising, 26th July to 22nd August 1897 on the North-West Frontier of India

Commanders in the Malakand Rising: At the time of the outbreak, the Indian Army garrison at Malakand and Chakdara was commanded by Brigadier-General William Meiklejohn. The Malakand Field Force was commanded by Major-General Sir Bindon Blood KCB. The uprising seems to have been inspired by the Muslim cleric given the title by the British of the ‘Mad Fakir’ and other mullahs. One of the main non-religious leaders in the uprising was the Swati khan, Mian Gul.

Size of the forces in the Malakand Rising: Meiklejohn’s

force at Malakand and Chakdara numbered around 2,750 men. The troops

sent up from Mardan under the command of Colonel Reid numbered a further

1,200. The additional troops making up the balance of the Malakand

Field Force under General Blood numbered around 5,000. 4 batteries, 3

of mountain artillery, accompanied the Force with 24 guns.

The number of tribesmen built up during the attack on Malakand to around

20,000. Numbers then fell away as the British advanced.

Major-General Sir Bindon Blood KCB, commander of the Malakand Field Force: Malakand Rising, 26th July to 22nd August 1897 on the North-West Frontier of India

Winner of the Malakand Rising: The British and Indian Army.

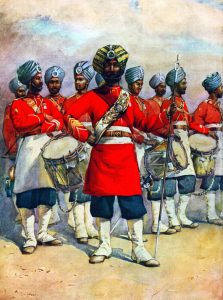

Uniforms, arms and equipment in the Malakand Rising:

The British military forces in India fell into these categories:

- Regiments of the British Army in garrison in India. Following the Indian Mutiny of 1857, India became a Crown Colony. The ratio of British to Indian troops was increased from 1:10 to 1:3 by stationing more British regiments in India. Brigade formations were a mixture of British and Indian regiments. The artillery was put under the control of the Royal Artillery, other than some Indian Army mountain gun batteries.

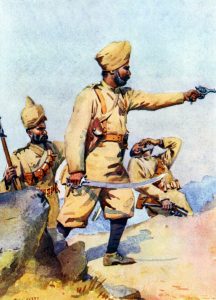

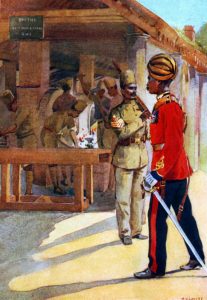

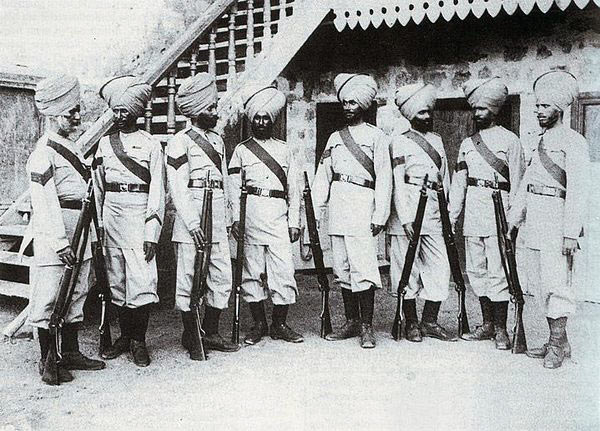

- The Indian Army comprised the three armies of the Presidencies of Bombay, Madras and Bengal. The Bengal Army, the largest, supplied many of the units for service on the North-West Frontier. The senior regimental officers were British. Soldiers were recruited from across the Indian sub-continent, with regiments recruiting nationalities, such as Sikhs, Punjabi Muslims, Pathans and Gurkhas. The Indian Mutiny caused the British authorities to view the populations of the East and South of India as unreliable for military service.

- The Punjab Frontier Force: Known as ‘Piffers’, these were regiments formed specifically for service on the North-West Frontier and were controlled by the Punjab State Government.

- Imperial Service Troops of the various Indian states, nominally independent but under the protection and de facto control of the Government of India. The most important of these states for operations on the North-West Frontier was Kashmir.

A British infantry battalion comprised 10 companies with around 700 men and some 30 officers. A battalion had a maxim machine gun detachment of 2 guns and around 20 men.

Indian infantry battalions had much the same establishment, without the Maxim gun detachment. Senior officers were British, holding the Queen’s Commissions. Junior officers were Indian.

In 1897, Indian infantry regiments carried the single shot, drop action Martini-Henry breech loading rifle. British regiments had received the new Lee Metford bolt action magazine rifle from 1894.

By 1897, both Indian and British Royal Artillery Mountain Batteries used the RML (Rifled Muzzle Loading) 2.5 inch gun, the successor to the small, basic and unreliable RML 7 pounder gun, which had gone out of service in the British batteries in the early 1880s and, finally, in the Indian batteries in around 1895. The 2.5 inch had the nickname of ‘the Screw Gun’ as the barrel came in two sections that were screwed together for firing. The gun was dismantled for transport and carried by mules (see Kipling’s poem ‘the Screw Guns’).

British and Indian troops in 1897 wore khaki field dress when campaigning, with a leather harness to carry equipment and ammunition. British troops wore a pith helmet. Indian troops were largely turbaned. Gurkha troops wore a pill box hat. Scottish Highland regiments wore the kilt. Scottish Lowland Regiments, such as the Highland Light Infantry and the King’s Own Scottish Borderers, wore tartan trews.

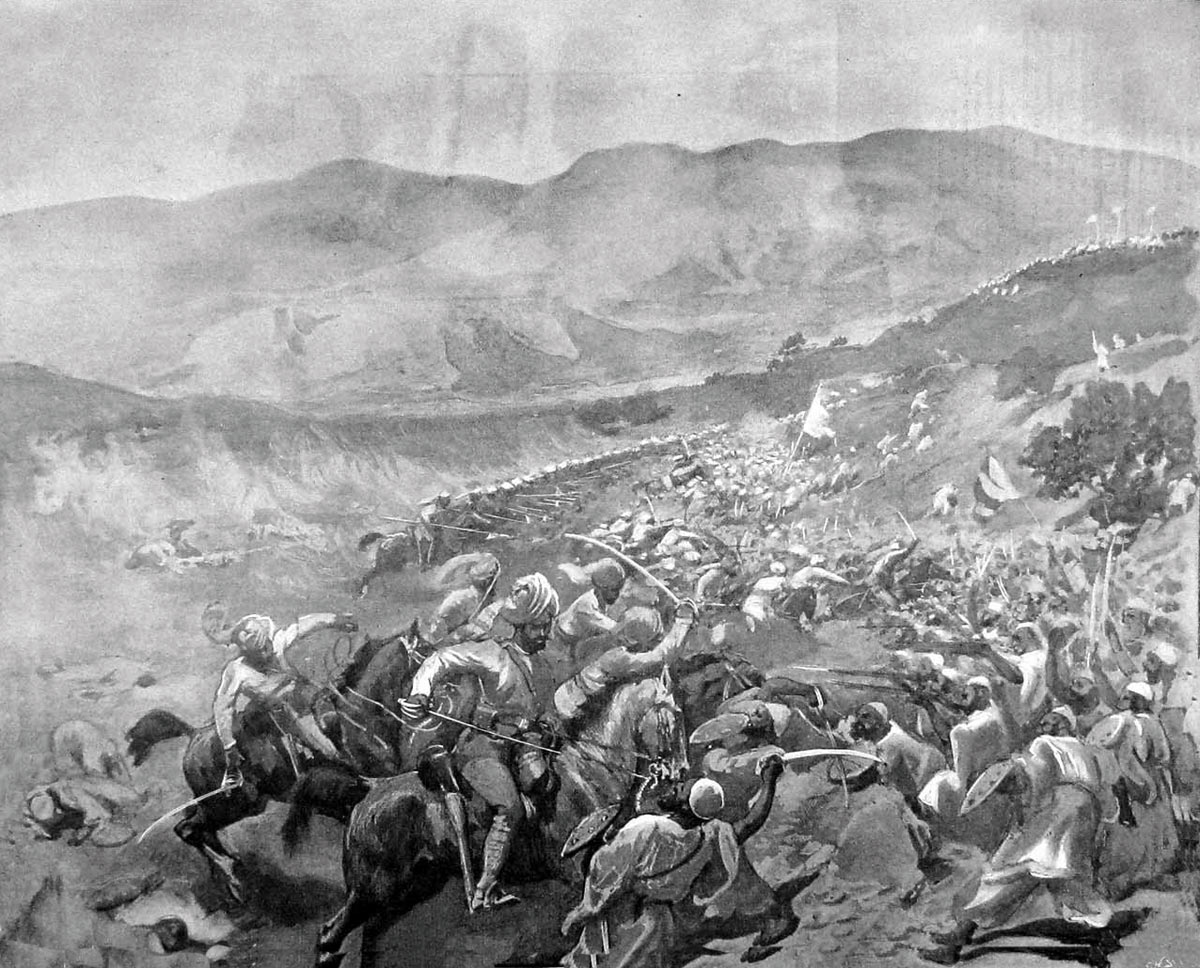

The Indian cavalry regiments were armed with lance, sabre and carbine.

The standard tactic used by the British and Indian armies on the North-West Frontier of India, as with other so-called ‘semi-civilised enemies’ (tribesmen armed with swords and lances and with limited access to modern firearms), was to deliver a frontal attack, discharging controlled volleys of rifle fire and charging home with the bayonet. When stationary under fire, cover was taken behind sangars or low, stone-built walls.

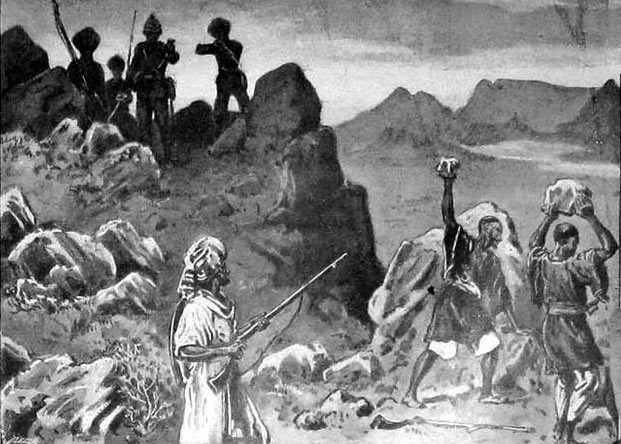

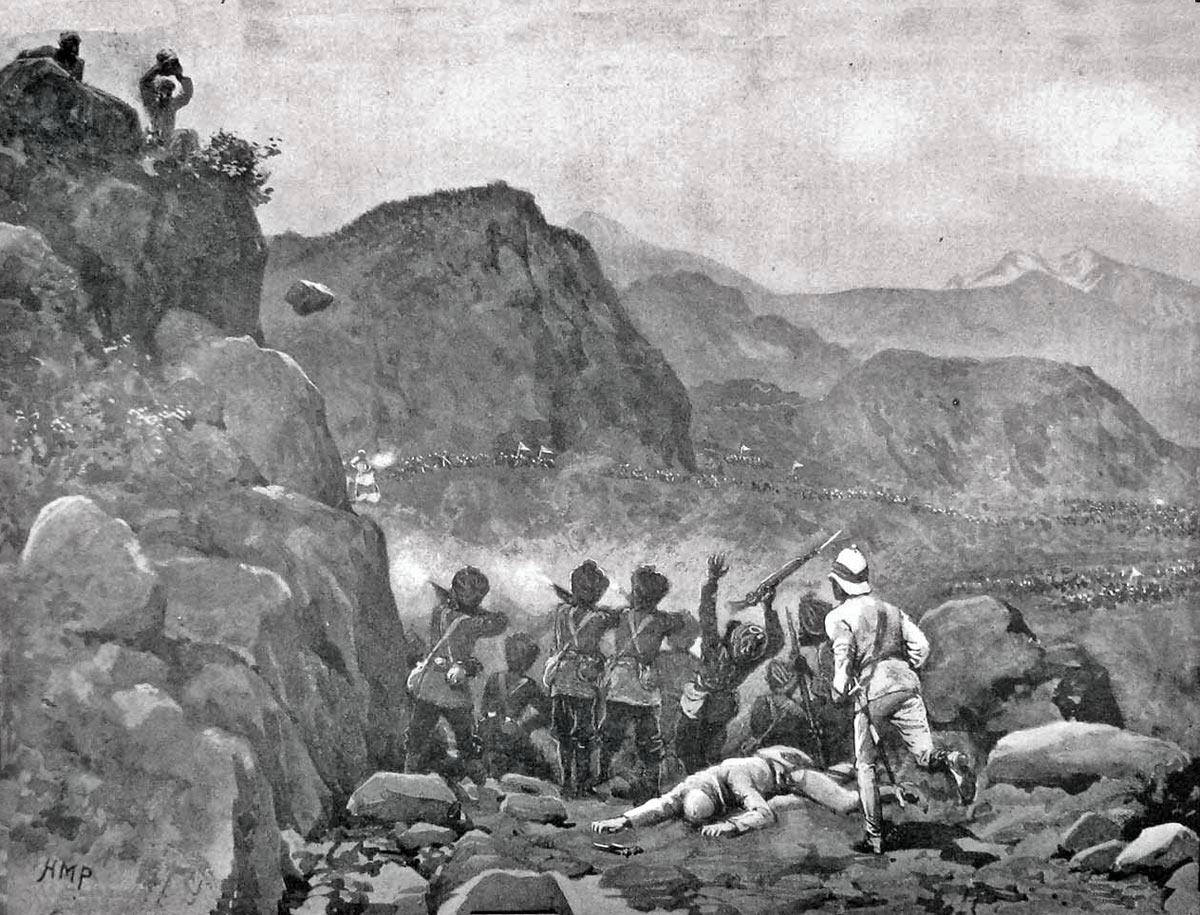

Tribesmen surprised in the Swat Valley: Malakand Rising, 26th July to 22nd August 1897 on the North-West Frontier of India

Supporting fire was provided by artillery, where available. Cavalry conducted scouting duties and, in suitable circumstances, delivered mounted charges, which were particularly effective against loose formations of tribesmen caught in flat open country. The Indian cavalry regiments were adept at mixing mounted action with dismounted, in which carbine fire was used against tribesmen, particularly during a withdrawal.

When a military column moved through hostile country, great care had to be taken to ensure that flanking high ground was occupied in strength, until the column was clear of the area.

Withdrawal was when troops became most vulnerable. Experienced units made sure that withdrawal was made by alternate leaps, so that there was always a force providing covering fire for the troops moving back. Pathan tribes were quick to follow up British withdrawals and any error was immediately exploited. Many of the problems in battle for the British arose from inexperienced regiments failing to comply with the exacting requirements of frontier warfare.

Rescue of the officers at Landakai on 17th September 1897: Malakand Rising, 26th July to 22nd August 1897 on the North-West Frontier of India

The tribesmen fought on foot. It is estimated that, in the Malakand campaign, around a half were in possession of firearms: muskets, jezails, some Sniders (Enfield rifled muskets converted to breach loading) and a few Martini-Henry rifles. The tribesmen possessed no artillery or machine guns. Many fought with swords. Flags representing villages, clans and tribes were carried in battle as rallying points. Drums of many sorts were beaten; pipes and trumpets played.

A feature of warfare on the North-West Frontier of India was the ability of tribesmen to assemble in large numbers with little warning and to move at disconcerting speed across mountainous terrain, even at night.

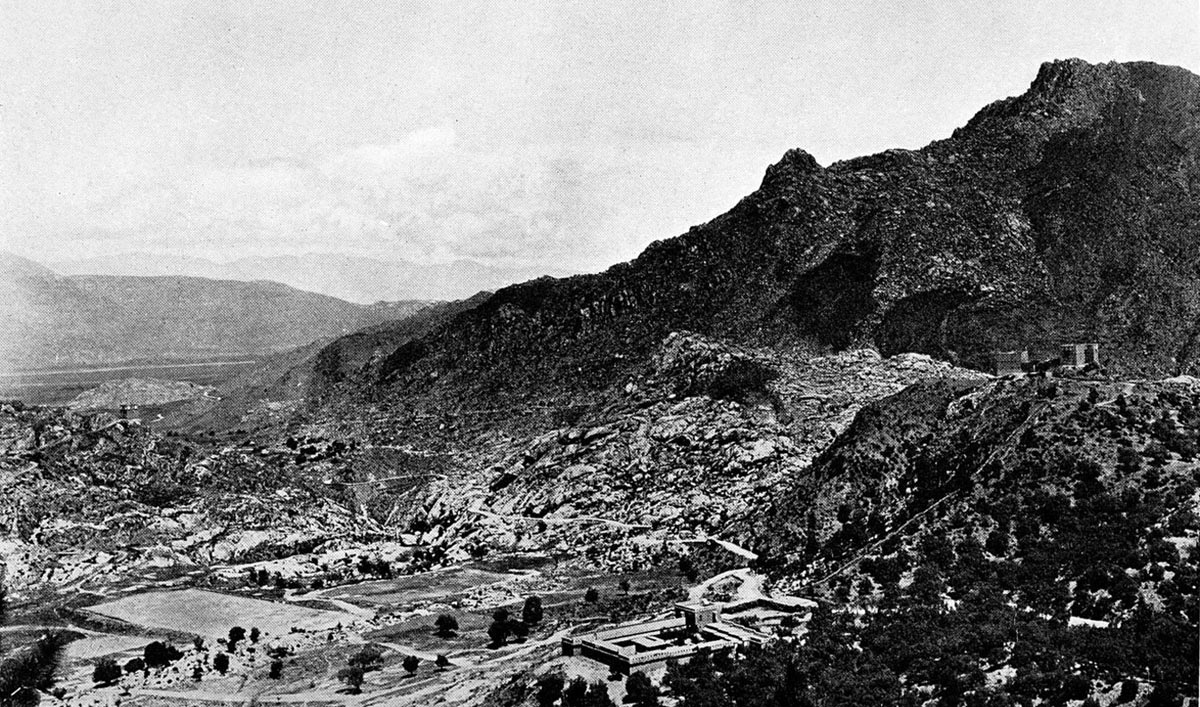

Map of the Malakand Rising, 26th July to 22nd August 1897 on the North-West Frontier of India: map by John Fawkes

The drums of the 45th Rattray’s Sikhs: Malakand Rising, 26th July to 22nd August 1897 on the North-West Frontier of India: picture by AC Lovett

Background to the Malakand Rising:

In 1897, the North-West Frontier of India erupted in warfare, the tribes

along the border attacking British garrisons and Indian villages. The

reaction to this uprising was a series of incursions by the British into

tribal territory in 1897 and 1898.

The first incident in the series of uprisings was the action at Maizar in the Tochi Valley, where, on 10th June 1897, the inhabitants of a group of Madda Khel villages attacked a small British force.

Following this incident, the British were involved in campaigns during

1897-8 in the Tochi Valley, in the Tirah against the Afridis, in the

Malakand and Swat Valley (this account), against the Mohmands and

finally the Bunerwals.

The Government of India identified several factors leading to the uprisings. The Amir of Afghanistan in the late 1880s penned a book urging Muslims in the border regions to wage ‘jihad’ against the British. The Amir claimed to the British that the book was to preserve his own precarious position amongst fanatical Afghans.

Numbers of Muslim mullahs in the independent tribal regions along the border of India preached ‘jihad’ against the British and invoked the Amir’s book.

In Lower Swat, a Bunerwal Mullah called Sadullah established himself at Landakai and sought to raise the tribes against the British, other religious leaders contributing to his efforts. This Mullah was referred to by the British as the ‘Mad Fakir’. This form of label was a consistent British practice in the late 19th Century. Any Muslim leader who fought against the British at this time, whether in the Indian sub-continent, the Sudan, Somalia or Eritrea, was liable to be given a nickname by British officials that suggested that he was deranged.

On the other hand, it seemed that the ‘Mad Fakir’ made claims to the tribesmen that suggested that he was near-divine. He also seems to have informed the tribesmen that the garrisons at Malakand and Chakdara contained the only troops the British had.

The Government of India concluded that the immediate trigger for the uprisings was the victory of the Turks over the Greeks in the eastern Mediterranean, a potent symbol of Muslim success over the Christian infidel.

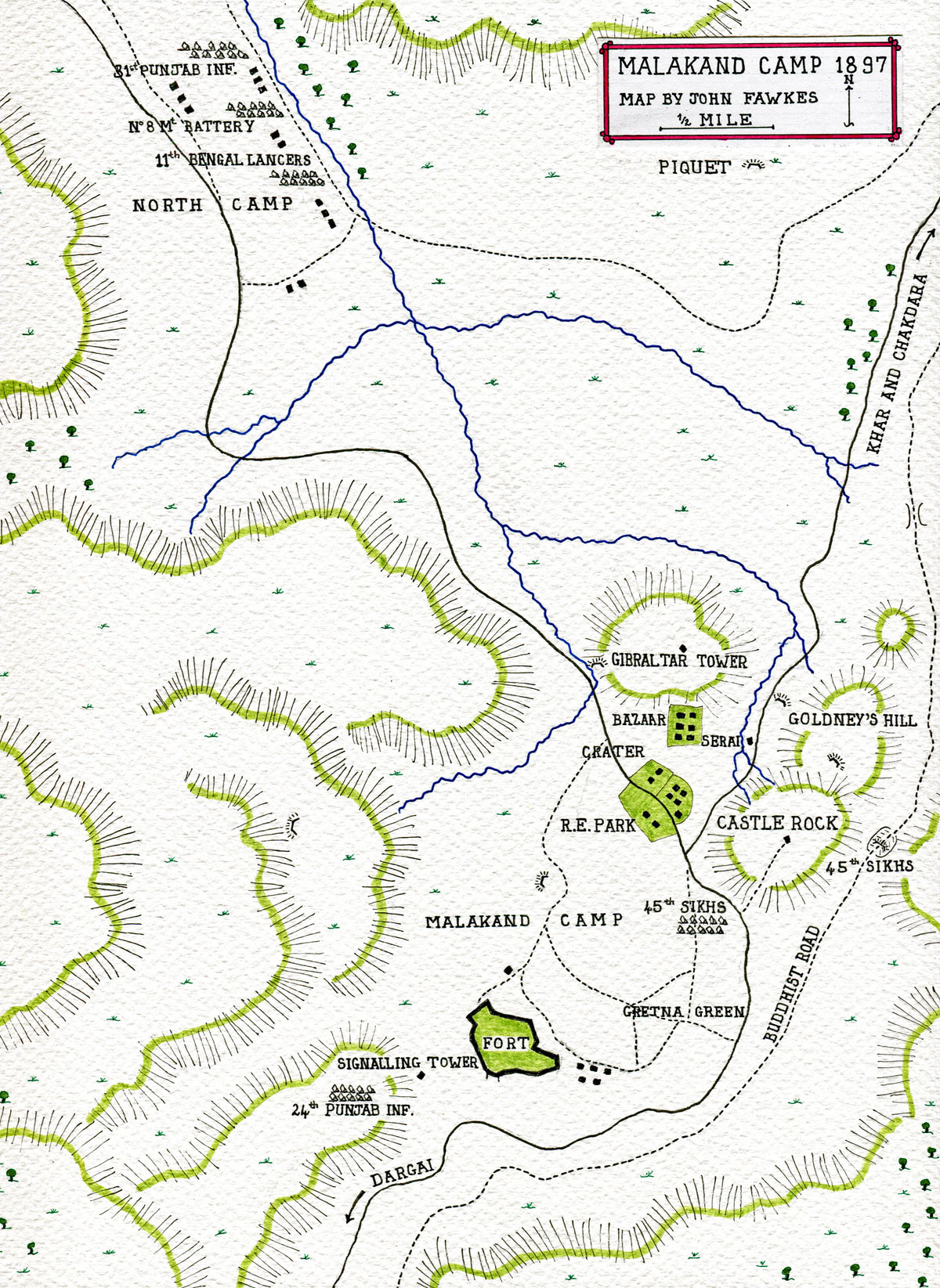

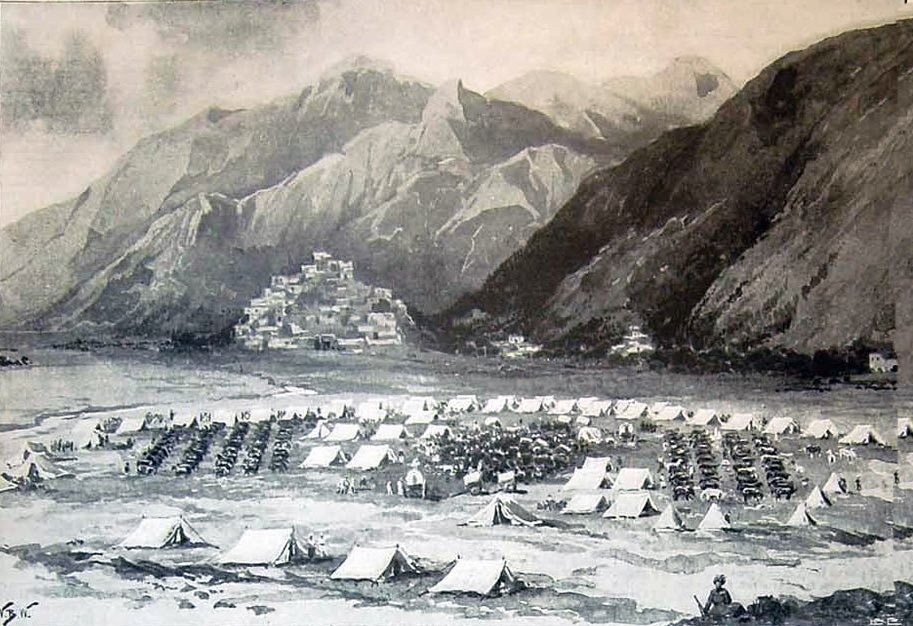

Malakand Camp seen from Malakand Fort, looking north towards the Swat River Valley: Malakand Rising, 26th July to 22nd August 1897 on the North-West Frontier of India

Of background importance was the concern of the border tribes at the threat to their independence from the increasingly intrusive British presence in the area.

The British found tribal dissatisfaction hard to reconcile with the growing prosperity of the area from the increase in trade with British India during the 1890s.

Guides Infantry and Guides Cavalry: Malakand Rising, 26th July to 22nd August 1897 on the North-West Frontier of India: picture by AC Lovett

After the 1895 Chitral campaign, the British maintained a garrison in Chitral town. To support this post, a road was established through Swat and Dir to the Chitral valley. The road was guarded through tribal territory by local levies, paid for by the Government of India. At the southern end of the road, the British built a fort and camp at the top of the Malakand Pass and a fort at the Chakdara crossing of the Swat River. A graded road was built from Dargai to the Chakdara Bridge, via Malakand and the Amandara Defile.

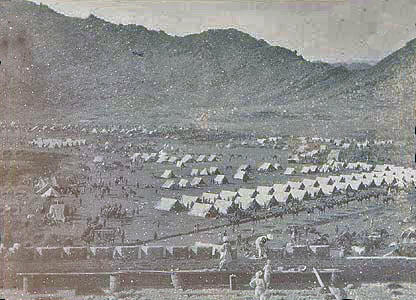

At the beginning of 1897, the Malakand Camp was garrisoned by an Indian brigade. The fort overlooked the Malakand Pass, with most of the brigade encamped in the volcanic bowl beneath the fort. An additional camp, called Malakand North Camp, lay in the valley to the north-west of the main camp.

The British encampment at Malakand, from its establishment in 1895 during the Chitral operation, grew by default and without proper planning. The fort, on a spur running down from the Malakand Kotal, was the only permanent structure and accommodated 200 men. The rest of the brigade lived in tents and huts in the main camp, on the floor of the crater immediately below the fort and in the North Camp.

As with any cantonment in India, a bazaar was established by civilian traders, to supply the troops. A Serai provided accommodation for visitors. A commissariat camp contained the brigade’s supplies of food and clothing. The Royal Engineers park contained the engineering stores and reserves of ammunition and weapons.

Account of the Malakand Rising:

The Attack on the Malakand Camp:

Colonel William Meiklejohn of 20th Punjab Infantry (see

Waziristan 1894) commanded the Malakand Brigade, as temporary

brigadier-general, with troops situated at Malakand, North Malakand,

Chakdara and Dargai, comprising the 24th Punjab Infantry, the 45th Sikh Infantry, No. 5 Company Madras Sappers and Miners, the 31st Punjab Infantry, No. 8 Bengal Mountain Battery and 1 squadron of the 11th Bengal Lancers.

Map of Malakand Camp: Malakand Rising, 26th July to 22nd August 1897 on the North-West Frontier of India: map by John Fawkes

200 men of the 24th Punjab Infantry formed the garrison in the Malakand fort. The remainder of the 24th Punjabis, with the 45th Sikh Infantry and the Sappers and Miners, were encamped in the Crater. The 31st Punjab Infantry, 1 squadron of 11th Bengal Lancers and the mountain battery were in the North Camp.

Malakand Camp South seen from the fort: Malakand Rising, 26th July to 22nd August 1897 on the North-West Frontier of India

Lieutenant Rattray commanded the garrison at Chakdara Fort, guarding the bridge over the Swat River, with 180 sepoys of the 45th Sikhs and 20 sowars of the 11th Bengal Lancers. 200 men of the 31st Punjab Infantry garrisoned Dargai, on the road from Nowshera to Malakand.

A political officer, with responsibility for the area, Major Deane, operated from Malakand Camp.

In early summer 1897, information came in to the British at Malakand, from Swat and other tribal areas that the ‘Mad Fakir’ was attracting large crowds for his addresses, urging holy war against the British. Pathans serving with the regiments at Malakand warned their officers of an impending tribal uprising.

26th July 1897:

On 26th July 1897, British officers from Malakand and

Chakdara assembled to play polo on the garrison ground at Khar, a

village on the road between Malakand and Chakdara. At the end of the

game Lieutenant Rattray received a note from 2nd Lieutenant

Wheatley, that Chakdara Fort was being threatened by a large force of

tribesmen. The officers returned to their posts, Rattray passing

several large gatherings of armed tribesmen on his ride to Chakdara.

Brigadier-General Meiklejohn telegraphed to Mardan, for the Guides to come up to Malakand and prepared to dispatch the 45th Sikhs to seize the pass at Amandara, on the road between Malakand and Chakdara.

Lieutenant Colonel McRae of the 45th Sikhs: Malakand Rising, 26th July to 22nd August 1897 on the North-West Frontier of India

Before the 45th Sikhs could leave, at around 10pm, a jemadar of the local levies arrived, with the news that the Mad Fakir was approaching Malakand with a large force of tribesmen. Buglers blew the assembly, for the garrison to take its alarm positions.

The main Malakand camp was accessed from the north by two routes. One was the main graded road from Khar into the centre of the camp. The other was the old Buddhist road which led up to the edge of the crater, on the east side of the camp. Both routes were points of vulnerability for the garrison.

On hearing the assembly, Lieutenant-Colonel McRae, commanding the 45th Sikhs, rushed to his regiment’s guardroom and ordered the guard piquet to the edge of the crater, to hold the Buddhist road against any tribesmen advancing up the road. The piquet was led off by Major Taylor. Colonel McRae gathered such other soldiers as he could find, left orders for the whole regiment to follow, and hurried after Taylor.

McRae and Taylor arrived, with their handful of Sikh soldiers, at the top of the crater rim to find a large body of tribesmen climbing the road from the opposite direction. The Sikhs took up a defensive position in a cutting, where the tribesmen were unable to deploy and opened fire.

45th Sikhs holding the piquet on the Budhist Road into Malakand Camp: Malakand Rising, 26th July to 22nd August 1897 on the North-West Frontier of India

The Sikh troops were able to hold back the mass of tribesmen, until more of their comrades arrived under Lieutenant Barff.

The party of 45th Sikhs fell back to a stronger position, maintaining a fire which kept the tribesmen back. McRae’s Sikhs were about to be overwhelmed when the rest of the regiment arrived. The position was then firmly held against the attackers. This dramatic episode prevented the Malakand garrison from facing a flood of tribesmen pouring into the camp from the east rim.

In the centre of the camp, the tribesmen rushed up the Khar Road into the crater. The piquet of the 24th Punjab Regiment on the road was driven back and the tribesmen flooded into the bazaar and the Serai.

Other tribesmen climbed the hills on either side of the road and began a fire into the camp, which would continue for several days until the assault on Malakand ended.

The noise was overwhelming with drums beating and pipes playing. A bugler was heard in the ranks of the tribesmen, playing all the calls of the British Army in turn. The bugler was part way through the ‘Officers’ Mess call’, when he abruptly ceased, presumably shot.

Sir Skipton Climo DSO as a retired lieutenant general: Malakand Rising, 26th July to 22nd August 1897 on the North-West Frontier of India

Lieutenant Climo led a company of the 24th Punjabis across the camp football pitch and cleared the bazaar of tribesmen at the point of the bayonet. The tribesmen renewed the assault on the bazaar in greater numbers and Climo’s company was driven back.

The tribesmen advanced on the defended area and entered the Commissariat Hut, where the Brigade Commissariat officer, Lieutenant Manley, was killed. Other tribesmen captured the Quarter Guard Hut of the Sappers and Miners, with the company’s ammunition reserve.

Brigadier-General Meiklejohn organised a party to retake the Quarter Guard, comprising his orderly, Captain Holland and Lieutenant Climo, both of the 24th Punjabis and a handful of soldiers from the 24th, 45th Sikhs and the Sappers and Miners. The first counter-attack failed. Captain Holland was severely wounded and several of the soldiers killed or wounded. The general was struck on the neck.

Lieutenant Climo led two further assaults with soldiers from his regiment, the 24th Punjabis, the second of which succeeded in re-taking the Quarter Guard. The tribesmen had removed the ammunition.

The garrison now held the stockaded areas on the south side of the road, the Royal Engineers Park and the Commissariat in the centre of the crater. The tribesmen occupied the crater rims from which they fired down into the area held by the troops. Major Herbert the DAAG was hit, as was Lieutenant-Colonel Lamb, the Commanding Officer of the 24th Punjab Infantry. Command of the 24th devolved on Lieutenant Climo, as the senior unwounded officer. Climo was 29 years of age.

At around 1am, it was realised that a havildar of the 24th was lying wounded on the edge of the football pitch near the bazaar. Lieutenant Costello, of the 26th Punjabis but attached to the 24th, took 2 soldiers of the 24th and brought the havildar back despite a heavy fire, for which he received the Victoria Cross and the 2 soldiers received the Indian Order of Merit.

After dark, Lieutenant Rawlins was sent up to the fort to bring down 100 men from the garrison, to re-enforce the camp. Evading, with some difficulty, the tribesmen on the hillside between the camp and the fort, shooting some of them, Rawlins returned with the 100 men.

24th Punjabis: Malakand Rising, 26th July to 22nd August 1897 on the North-West Frontier of India: picture by AC Lovett

27th July 1897:

Around 4am, the tribesmen withdrew from the bazaar, carrying their

casualties and the firing fell away. At dawn 2 companies of the 24th Punjabis cleared the bazaar of stragglers and rescued the surviving traders, hiding in their booths.

With dawn, a force commanded by Major Gibbs moved out from the North Camp, which had not been attacked, comprising the 31st Punjab Infantry, 2 guns and 40 sowars of the 11th Bengal Lancers and supported by a wing of the 24th Punjab Infantry.

Gibb’s force advanced up the valley to the north, to clear it of tribesmen. It was only then that it became clear how immense was the number of tribesmen and Major Gibbs’ force was compelled to fall back, other than the small squadron of the 11th Bengal Lancers under Captain Wright, which went on to Chakdara, to re-enforce the garrison. The tribesmen attempted to interfere with Gibbs’ withdrawal by attacking from the high ground.

Lieutenant Climo led a counter-attack with 2 companies of the 24th, pushing the tribesmen back.

In view of the information now brought in to him on the scale of the tribal uprising, Brigadier-General Meiklejohn directed that the North Camp be abandoned and the troops withdrawn to the main camp as quickly as possible. This was a tough order. The regiments had been living in the North Camp for some time and had a substantial amount of kit with them. It took time to pack this up and there was no transport available for the move.

At 8.30am, the Guides Cavalry completed their 37 mile journey from Mardan and marched into Malakand Camp. Other regiments, mobilised by the Government of India, were moving to assist in the relief of the Malakand garrison.

The abandonment of the North Camp was taking too long, in view of the imminent threat from the hordes of tribesmen and, at 4pm, the order was given to evacuate the camp without further delay. By this time a substantial number of tribesmen, particularly Utman Khels, were advancing on the camp. As the garrison of the North Camp withdrew the short distance to the Crater, it was closely pursued by the tribesmen, while covering fire was provided by the 24th Punjab Infantry.

Badge of the 24th Punjabis: Malakand Rising, 26th July to 22nd August 1897 on the North-West Frontier of India

The Guides infantry (260 men), commanded by Lieutenant Elliot-Lockhart, arrived at Malakand at 7.30pm, having marched from Mardan at 2am (the march was 32 miles in blistering heat). 50 of the Guides were left at Dargai to bolster the garrison there.

On the evening of 27th July 1897, the tribesmen gathered, in even greater numbers, along the road from Chakdara and Khar, to resume the attack on the Malakand garrison. The North Camp was in flames, after being looted. Numerous tribesmen fired down on the camp from the hills and the crater rim.

The regiments were in much the same formation as on the night before. Lieutenant-Colonel McRae and his 45th Sikhs, with 2 guns, held the Buddhist Road, at the top of the crater rim, on the right of the position. The 24th Punjab Infantry, now commanded by Lieutenant Climo, following the wounding of Lieutenant-Colonel Lamb, held the area of the road to the North Camp.

In the centre of the garrison’s position, the 31st Punjab

Infantry, No. 5 Company, Queen’s Own Sappers and Miners, 2 guns and the

Guides defended the graded road and the various compounds.

The bazaar was abandoned. A piquet of 24 men from the 31st Punjab Infantry, commanded by Subadar Syed Ahmed Shah, held the Serai.

At 8pm, the tribesmen attacked along the whole defensive line. The 45th

Sikhs were pressed hard, many tribesmen fighting their way into the

Sikh positions, until killed or driven back at the point of the bayonet

and subjected to salvos from the 2 guns.

In the crater, the tribesmen swept through the bazaar and attacked the Serai held by Subadar Shah’s piquet. Only when 20 of his men were dead or wounded, did the subadar, himself injured, order his men to evacuate the building by way of a ladder over the back wall, taking the wounded with them.

On the left, the 24th Punjab Infantry were heavily attacked. Lieutenant Climo took 2 companies and led them in a counter-attack beyond the breastwork. Churchill records that Climo’s force drove the tribesmen back some two miles. However, it seems unlikely that such a small force would have gone so far from the camp, however successful their attack.

At the end of that night, the tribesmen held the Serai, but, otherwise, the Malakand garrison stood where it was at the beginning of the attack. The tribesmen suffered significant casualties which could not be assessed.

28th July 1897:

The tribes identified by the Malakand Garrison included Swatis, Utman

Khels, Mohmands, Salarzais and others. During the course of 28th

July, large numbers of Bunerwals could be seen in the opposing ranks

for the first time. The Bunerwals were easily identified, wearing black

or dark blue clothes against the white worn by most of the other

tribes.

During the day, the garrison strengthened and improved the defences of the camp, while the tribesmen sniped at the troops.

At 10pm, the tribesmen renewed the assault along the whole of the defended line. The attacks continued throughout the night, until the tribesmen withdrew to the surrounding hills, just before dawn. British casualties were 2 soldiers killed and 3 British officers and 13 men wounded. No pursuit was possible due to the exhaustion of the troops.

29th July 1897:

During the day, further work was carried out on the defences. Bonfires

were prepared, to be lit when the next attack was launched, thereby

illuminating the battlefield. Signalling was resumed with Chakdara

Fort, which reported that it was successfully holding out.

In the afternoon, a squadron of the 11th Bengal Lancers reached Malakand, with 12,000 rounds of ammunition carried in the sowars’ saddle bags.

In the evening, the 35th Sikhs, the 38th Dogras and more Guides arrived at Dargai, but in a state of exhaustion. The 35th Sikhs, who had marched up from Nowshera, had 21 fatal casualties from heat stroke.

Piquet of Guides Infantry on the Buddhist Road near Castle Rock: Malakand Rising, 26th July to 22nd August 1897 on the North-West Frontier of India: picture by Edmund Hobday

That night, the bonfires were lit to illuminate the attackers. As a result, the tribesmen initially directed their assault around the flank of the position held by the 24th Punjab Infantry. This attack was driven off.

At 2am, a desperate attack was made on the main defences. After half an hour, the attack was abandoned. It was heard later that the ‘Mad Fakir’ led this assault himself and had been shot in the hand, retiring with his injury to Landakai. His chief companion, designated by the ‘Mad Fakir’ to be crowned King in Delhi once the uprising succeeded, was killed.

British casualties were 2 officers severely wounded and 1 soldier killed and 17 soldiers wounded.

Badge of the 31st Punjabis: Malakand Rising, 26th July to 22nd August 1897 on the North-West Frontier of India

30th July 1897:

200 soldiers of the 31st Punjab Infantry marched up from

Dargai to Malakand and began to assist in the repair of the defences.

During the day, the fire from the tribesmen on the hills and the crater

rim was noticeably less than on previous days.

In the afternoon, the tribesmen appeared in greater numbers than before, confirming reports that re-enforcements from Buner were joining the attackers. The attack on the camp was resumed that night, but not pressed with the same vigour as on previous nights.

31st July 1897:

Lieutenant-Colonel Reid arrived at Malakand Camp, with the remaining 700

men of the reinforcements, leaving 400 men at Dargai. Firing continued

during the day, but there was no attack that night.

1st August 1897:

At around 11am, a force left Malakand to relieve Chakdara, comprising the Guides Cavalry and 1 squadron of the 11th

Bengal Lancers, a force of 250 men. Lieutenant-Colonel Adams of the

Guides commanded the force. 3 battalions of the infantry and the

mountain battery prepared to follow.

The cavalry was ordered to make a dash for the Amandara Defile. This move was anticipated by the tribesmen, who attacked the cavalry in great strength, while they were still in the hills.

Despite the difficult ground, the Guides delivered a charge, killing around 100 tribesmen, with losses of 1 sowar killed and 2 officers and 12 sowars wounded. The tribesmen continued to press on, until the numbers surrounding the small cavalry force compelled the sowars to dismount and drive them back with carbine fire.

It was clear that the cavalry were too few and the day too far advanced, to achieve a breakthrough to Chakdara before nightfall and Adams returned to Malakand. The squadrons executed a withdrawal in turn, covering each other with dismounted carbine fire.

The Siege of Chakdara Fort:

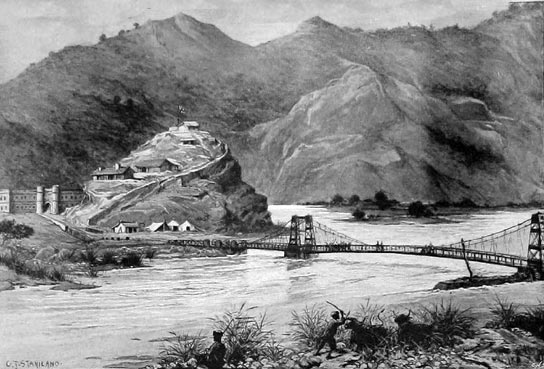

In 1895, when the Chitral Relief Force crossed the mountain line from

Malakand into the valley of the Swat River, it was immediately apparent

that there needed to be a permanent crossing point on the river.

Chakdara Fort and bridge over the Swat River: Malakand Rising, 26th July to 22nd August 1897 on the North-West Frontier of India

At the end of the Chitral operation, a 500 yard suspension bridge was built over the Swat River near the village of Chakdara. A fort was built on the small hill at the north end of the bridge, with a signalling tower on the hillside above the fort.

The description of the fort in the Official Government of India history states: “This fort, which was built of stone, was situated on a small rocky knoll on the right bank of the river, and about 150 yards from the end of a spur which descends from the high hills on the west. On the north-west and west faces were double-storied barracks with rows of loopholes and arrangements for flanking fire. The north-east side of the knoll was steeply scarped and protected by a wall and barbed wire fence, while on the south was a small hornwork. About 500 yards away, on the spur to the west, was a small one-storeyed blockhouse, used as a signalling tower, from which communication was maintained with the Malakand. On the left bank of the river the entrance to the bridge was guarded by a loopholed iron gate with a blockhouse on either side.” One of these bridge blockhouses took 1 of the fort’s 2 Maxim guns. The other Maxim gun and a 9 pounder field gun were mounted on a platform in the main fort.

The weakness of the fort was that it was dominated by the cliff on which the signal tower stood. Tribesmen on the ridge could see and fire directly into every open area of the fort.

26th July 1897:

On 26th July 1897, the day of the outbreak, the garrison of Chakdara Fort comprised around 210 men, 20 sowars of the 11th Bengal Lancers, 180 men of the 45th

‘Rattray’s’ Sikhs and several others and was commanded by Lieutenant

Haldane Rattray, the son of the officer who had raised the 45th Sikhs. Rattray’s second in command was Second-Lieutenant Wheatley of the 45th Sikhs. The medical officer was Surgeon-Captain Hugo. The Political Agent in the Fort was Lieutenant Minchin.

The first warning of possible trouble came with a message from the brigade headquarters on 23rd July 1897.

Sowar of the 11th Bengal Lancers riding through the tribesmen: Malakand Rising, 26th July to 22nd August 1897 on the North-West Frontier of India: picture by Richard Caton Woodville

On the evening of 26th July 1897, Rattray played polo at Khar, with fellow officers from Malakand. As the game ended, 2 sowars arrived with a message from Wheatley, saying that large numbers of tribesmen were closing in on the fort. Rattray galloped back to Chakdara, passing a large party of tribesmen, who took no notice of him. On Rattray’s return, a message was telegraphed to Malakand that Chakdara was about to be attacked and then the line was cut, outside the fort, by the tribesmen.

A Sikh havildar, out conducting survey work in the hills, was robbed of his sketching materials by a party of tribesmen and returned to the fort with a warning of tribal unrest.

A soldier of the Khan of Dir’s levies had promised to light a bonfire to warn of any impending attack. At 10.30pm that night, the bonfire was lit on the opposite hill. The garrison went to its alarm posts and soon afterwards, the tribesmen opened fire on the fort. The fort was to be under constant fire for a week.

The official Government of India record states in a footnote: “It may be interesting to note here that at 2am after the attacks had been made on the Malakand, the troops at Chakdara saw a fire balloon with a scintillating ball of intensely white light sent up from the top of a hill, about four miles off, adjoining the Swat valley. This was of course a pre-arranged signal for the tribes to rise…. The balloon must have been an imported article, this strange occurrence is a proof that the idea of a rising did not originate in the Swat valley itself, but was instigated elsewhere.”

Following the opening fusillade, the tribesmen rushed the fort, but were driven back. Further attacks during the night were made on the north-east corner of the fort and on the stable block. All were repelled with heavy casualties, inflicted on the tribesmen by controlled volley firing from the loop-holed walls. The assailants were identified as from the Adinzai valley and Khwazazai-Shamozai.

27th July 1897:

Captain Wright’s squadron of the 11th Bengal Lancers arrived in the fort with 40 additional sowars. Captain Baker of the 102nd

Bombay Grenadiers, the Malakand Transport Officer, accompanied Wright’s

squadron. Wright became the senior officer in Chakdara Fort, but left

the day to day command to Rattray, whose regiment formed most of the

garrison. Baker concentrated on working on the defences, to improve the

cover provided to the soldiers from the harassing fire from the high

ground behind the fort.

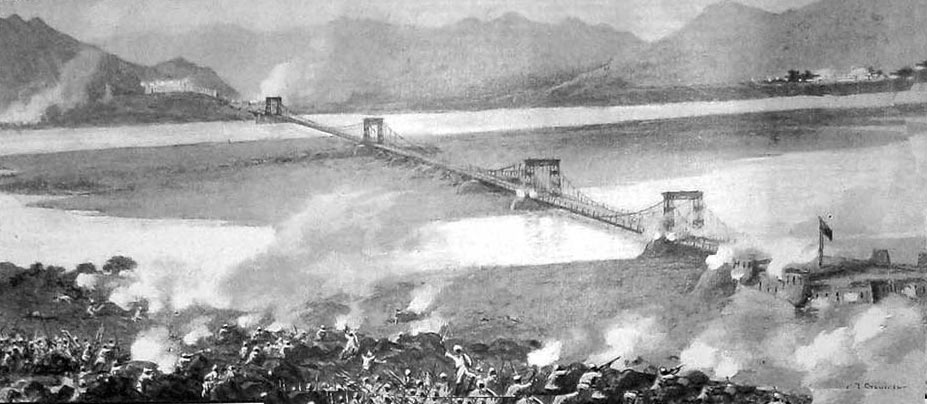

Chakdara Bridge under attack, seen from the south bank of the Swat River: Malakand Rising, 26th July to 22nd August 1897 on the North-West Frontier of India: picture by CJ Staniland

At 11.30am, the tribesmen launched a new attack on the north and east sides of the fort. They were driven off by the heavy defensive fire, many of the fanatical tribesmen shot down at the foot of the walls.

In addition to the assaults and rifle fire on the main fort, the tribesmen built stone sangars around the Signal Tower, from which they maintained an incessant fire at the tower, to prevent the occupants from gaining access to the signal platform on the roof and making contact by heliograph with the Malakand.

At midday, once the attack on the fort was repelled, a team took water and supplies up to the Signal Tower, under covering fire provided by the rest of the garrison and, in particular, by the 2 guns in the fort (1 Maxim and 1 Field). This re-supply was maintained daily until 1st August 1897, when the tribesmen completed their positions, so that it was impossible to make the short journey up the hillside to the tower.

The tribesmen massed for a further attack after nightfall. Second Lieutenant Wheatley noted the concentration points and, as soon as night came and the tribesmen began to move forward, the gun and the Maxim Gun opened fire, causing some 70 casualties. This fire did not prevent the attack, which came in, the tribesmen carrying scaling ladders to mount the wall, only to be repelled by the heavy musketry from the fort.

Lieutenant General Sir Bindon Blood and his staff: Malakand Rising, 26th July to 22nd August 1897 on the North-West Frontier of India

28th July 1897:

There was continuous firing all day, until, at 5.30pm, an attack was

launched, falling on the section of the perimeter manned by the sowars

of the 11th Bengal Lancers. The tribesmen came on in a

semi-circle, carrying some 200 flags representing many of the tribes on

this section of the border. The tribesmen rushed up to the fort and

several climbed into the compound, clambering over the barbed wire. The

attack lasted until dawn, when it fell away in the face of the

garrison’s fire. The attackers were identified as including men from

the Abazai, Khadakzai and Musa Khel clans.

British Mountain Battery: Malakand Rising, 26th July to 22nd August 1897 on the North-West Frontier of India: picture by Ernest Prater

29th July 1897:

The attack began at 3pm. Tribesmen emerged from Chakdara village,

carrying ladders and bundles of grass to throw on the barbed wire

entanglement. Again, the attack was unable to penetrate the defences.

A substantial group attacked the Signal Tower, working up to the walls and setting a large fire. The fire burnt itself out without any effect on the masonry of the tower, while the small garrison, aided by fire from the fort, inflicted significant casualties on the attackers. The attack ceased at around 5pm and the tribesmen withdrew, carrying as many of their casualties as they could, but still leaving some 50 dead around the Signal Tower.

30th July 1897:

The tribesmen appeared to be losing confidence in their ability to take

the fort. Although there was some desultory firing, an attack was not

launched until 5pm, enabling some of the garrison to rest for the first

time since the siege began. The attack had little of the ferocity of

the previous days and was over within a couple of hours. The attackers

were joined by tribesmen from Bajaur.

Sappers and Miners: Malakand Rising, 26th July to 22nd August 1897 on the North-West Frontier of India: picture by AC Lovett

31st July and 1st August 1897:

During these two days, the attackers were heavily re-enforced by

tribesmen from the Malakand and by members of the Malizai clan. From

around 1,500 tribesmen on the first day of the siege, the number of

attackers reached around 12,000 to 14,000. The attacks were less

frenzied and made greater use of cover and entrenchments to approach the

fort. The exhausted sowars and sepoys constantly fell asleep, to be

aroused by the British and Indian officers. There was no sign of a

relief column and no messages from the outside world.

On 1st August 1897, the tribesmen mounted an attack in which they captured the civilian hospital, a building near to the fort. The tribesmen loop-holed the walls of the hospital and used it to fire at the fort from close range.

The tribesmen were now in sufficient numbers to occupy the ridge above the fort, cutting off the signal tower and preventing any further supplies of water reaching the small garrison of the tower. From the ridge, fire could be maintained straight into the fort, which made any movement hazardous. It was apparent that these tribesmen were armed with Martini-Henry and Snider rifles.

A simple message was sent by heliograph to Malakand ‘Help us’.

2nd August 1897:

No doubt in view of the approach of the relief column from Malakand, early on 2nd

August 1897, the tribesmen launched a desperate attack on the fort in

large numbers. Bundles of grass were thrown on the barbed wire

entanglements and scaling ladders placed against the walls, combined

with a heavy fire from sangars on the ridge and all round the fort.

While the garrison sustained some casualties, substantial numbers of

tribesmen were shot down.

Late morning, the cavalry of the Guides and the 11th

Bengal Lancers were seen to be crossing the Amandara Ridge on the far

side of the river and to be galloping towards the fort, cutting down

parties of tribesmen in their path. Promptly Lieutenant Rattray had the

gates of the fort thrown open and led a party of his men in an assault

on the hospital, where some 30 tribesmen were bayoneted. Rattray then

led his party to attack the tribesmen in a sangar that was inflicting

casualties on the cavalry. One of the last tribesmen to be bayoneted

wounded Rattray in the neck.

The cavalry reached the fort and the siege was over.

The Signal Tower:

The Signal Tower was a square stone and masonry block house, built on

the ridge above the fort. The position of the Tower enabled contact by

heliograph (a signalling mechanism flashing Morse messages using the

sun’s rays on a mirror; only usable in sunlight, between stations in

view of each other) to be made with the Signal Tower at Malakand.

Heliograph or flag contact was possible with Chakdara Fort itself, which

was in full view of the Signal Tower.

Signalling Tower above Chakdara Fort: Malakand Rising, 26th July to 22nd August 1897 on the North-West Frontier of India

Entrance to the Signal Tower was by way of a door, 6 feet above the ground and a ladder that was drawn up. The Signal Tower walls were loop-holed and a gallery ran around the roof, projecting over the walls, with loop-holes in wall and floor, enabling the garrison to fire down on attackers. The garrison of the tower comprised 10 soldiers of the 45th Sikhs under Lance-Naik Vir Singh. This party was increased with a further 6 sepoys on news of the uprising. The tower contained a water tank which had not been filled prior to the attacks.

The Signal Tower was 500 yards up the hillside from the fort. A party took supplies of food and water up to the tower every day of the week-long siege, until the last day when the tribesmen built sangar positions to prevent access to the tower. The 9 pounder gun and the Maxim gun in the fort were able to fire in support of the Signal Tower.

Signalling Tower above Chakdara Fort: Malakand Rising, 26th July to 22nd August 1897 on the North-West Frontier of India

Churchill records that Sepoy Prem Singh went onto the tower roof every day, to signal to Malakand by heliograph, each time under a hail of fire. The signalling could only be carried out in full sunlight.

Casualties at Chakdara:

It was estimated that the tribesmen lost around 2,000 men in the week of

attacks on the fort. The casualties in the fort were slight: The 11th Bengal Lancers lost 1 man killed and 1 wounded. The 45th Sikhs lost 4 men killed and 10 wounded. Other casualties were 2 killed and 2 wounded.

The ride to Chakdara by Captain Wright’s squadron:

On 27th July 1897, Brigadier-General Meiklejohn ordered Major

Gibb to lead the garrison of the North Camp up the Chakdara Road and

drive away the tribesmen who had been attacking the Malakand during the

night. The squadron of the 11th Bengal Lancers under Captain Wright, with Captain Baker, the brigade transport officer, went on in advance.

Captain Wright’s squadron of 11th Bengal Lancers rides to Chakdara Fort: Malakand Rising, 26th July to 22nd August 1897 on the North-West Frontier of India: picture by Richard Caton Woodville

On reaching Bedford Hill, opposite the village of Khar, the infantry force under Major Gibb saw that large numbers of tribesmen were on the surrounding hills, threatening to cut the force off from Malakand and overwhelm it. Covered by Lieutenant Climo and his 2 companies of the 24th Punjab Infantry, who were providing support, the force managed to withdraw to the Malakand Camp, although under heavy attack. Wright’s squadron which was far in advance and moving at speed, carried on towards Chakdara.

As Wright’s lancers headed for the Amandara Ridge, which stretched in their path between the Swat River and the mountains and was usually negotiated by way of the Amandara Pass, it was apparent that the rising was on a massive scale. Every hill was occupied by tribesmen in arms.

As the squadron crossed the plain towards the Amandara Pass, it could be seen that the tribesmen were massed on the heights, ready to fire down on the lancers as they passed through the defile below them. The squadron might gallop through the defile, but there would inevitably be casualties who would have to be left behind.

Chakdara Fort seen from the north: Malakand Rising, 26th July to 22nd August 1897 on the North-West Frontier of India

A sowar informed Wright of a path at the end of the ridge, between the high ground and the Swat River. Wright resolved to take that route. The squadron veered to the left, heading for the end of the ridge. The watching tribesmen realised what was intended and started running along the crest of the ridge, towards the river.

The squadron reached the end of the ridge and headed along the path the sowar had described. After a distance, the path ended with a near sheer drop down to the river. Now committed to the route, the horsemen rode down the cliff face and found themselves on the edge of a gully. They rode down the gully which ended at a branch of the river, fast flowing and deep. The horses plunged in and swam across the branch.

The tribesmen reached the end of the ridge and began to fire at the squadron. The horsemen reached the far bank, to find themselves on an island. At the end of the island, the squadron crossed back to the bank they had left, now clear of the high ground. Here the sowars dismounted and returned the fire of the tribesmen, while Wright plunged into the stream, on his now seriously wounded horse, to rescue the hospital orderly and his pony, who were in trouble in the fast current.

Soldiers of the 35th Sikhs: Malakand Rising, 26th July to 22nd August 1897 on the North-West Frontier of India

The squadron continued along the bank, until the Maxim Gun in the bridge blockhouse at Chakdara came within range and gave covering fire, enabling the squadron to cross the bridge and join the Chakdara garrison.

As Captain Wright was now the senior officer in Chakdara Fort, he took nominal command, although he left the routine running of the garrison to Lieutenant Rattray. Captain Baker took on the role of improving the defences of the fort, in particular rigging up head cover where there was no loop-holing.

The Chakdara Relief Force:

The Government of India appointed Major-General Sir Bindon Blood KCB to

command the newly constituted Malakand Field Force and put down the

rising in Swat. General Blood lost no time in travelling from Agrah to

Malakand, arriving in the camp on 1st August 1897, the day

after the end of the all-out tribal assault on the Malakand Camp and the

day of Meiklejohn’s first attempt to relieve Chakdara Fort.

Reconnaissance by 11th Bengal Lancers and the Guides Cavalry on 1st August 1897: Malakand Rising, 26th July to 22nd August 1897 on the North-West Frontier of India: drawing by Edmund Hobday

Blood found that Meiklejohn was ready with a new force, to march to Chakdara at dawn the next day, 2nd August 1897. Blood approved the plan and directed Meiklejohn to command the force himself. The tribesmen appeared to threaten a further assault on the Malakand that night, firing into the camp and Meiklejohn’s force mustered under arms at midnight to counter any attack. The force comprised 2 squadrons of the Guides Cavalry, 2 squadrons of the 11t Bengal Lancers, 4 guns of No. 8 Bengal Mountain Battery, ½ company of No. 5 Company, Madras Sappers and Miners, 400 rifles of the 24th Punjab Infantry, 400 rifles of the 45th Sikhs and 200 rifles of the Guides Infantry.

At around 3am, the firing fell away and, at 5am, Meiklejohn’s column marched out of the Malakand Camp on the road to Chakdara.

General Blood directed the operation from a position on Castle Rock. On his orders, Colonel Goldney, with soldiers from the 35th Sikhs and the 38th Dogras, captured a hill (then named ‘Goldney’s Hill’) half a mile north of the camp, from where they provided covering rifle fire for the initial stages of Meiklejohn’s march, with the fire of 2 mountain guns positioned on Castle Rock.

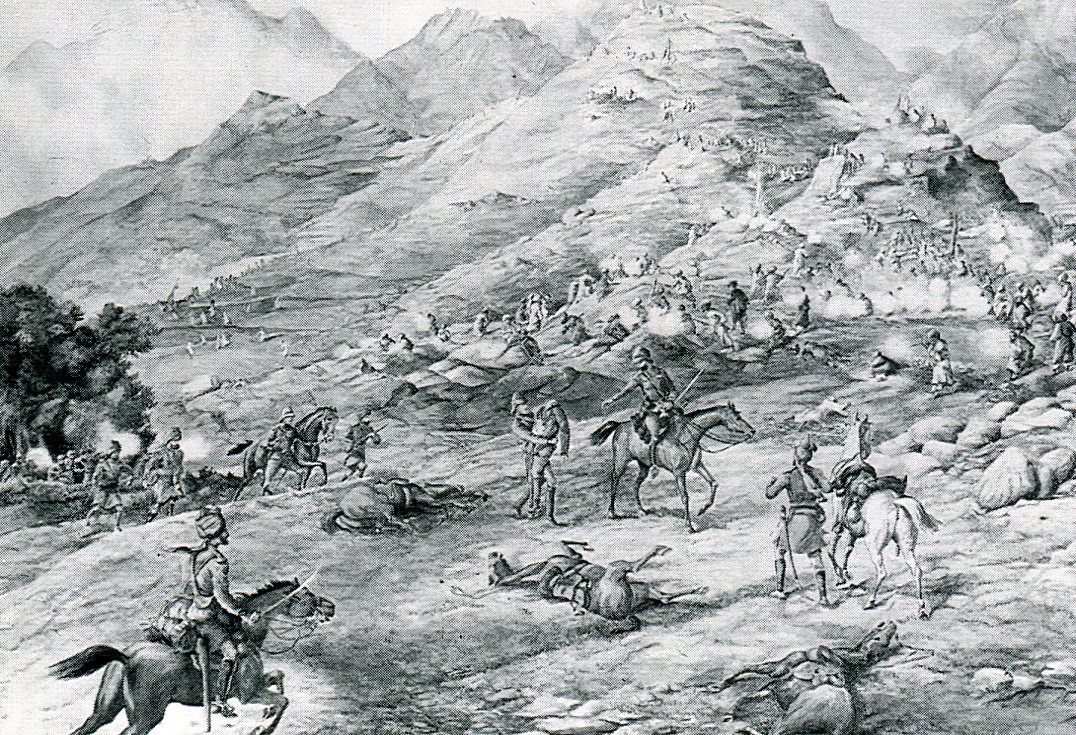

As in the previous attempt, the cavalry pushed on ahead to seize the Amandara Pass. The Guides Cavalry crossed Bedford Hill on the east side. Numbers of tribesmen moved hurriedly out of the way of these squadrons, to the west side of the hill, into the path of the 11th Bengal Lancers. Hard fighting took place, including one incident in which a tribesman, impaled on an 11th sowar’s lance, attempted to climb up the lance to strike at the sowar with his sword. This contest ended when an officer shot the tribesman with his pistol.

Troops from several regiments: Malakand Rising, 26th July to 22nd August 1897 on the North-West Frontier of India

As the infantry left Malakand Camp, tribesmen occupied the high ground at the junction of the Chakdara Road with the road to the North Camp. The Guides Infantry and the 45th Sikhs drove the tribesmen off the hill at the point of the bayonet, assisted by the supporting fire from Goldney’s Hill and Castle Rock. The tribesmen fell back to Malakot village on Bedford Hill. The 24th Punjab Infantry, the 45th Sikhs and the Guides Infantry attacked in line, driving the tribesmen off Bedford Hill into the Khar plain beyond, where they were pursued by the 4 squadrons of cavalry. Significant casualties were inflicted on the tribesmen in this sequence of attacks.

Lieutenant-Colonel Adams of the Guides, commanding the cavalry, pushed on across the Khar plain and seized the Amandara Pass. The infantry followed up, the 45th Sikhs taking, at the point of the bayonet, the village of Bat-Khela, from where fire had been directed at the passing cavalry squadrons.

Charge of the 11th Bengal Lancers and the Guides Cavalry in the relief of Chakdara Fortl: Malakand Rising, 26th July to 22nd August 1897 on the North-West Frontier of India

Adams pushed on with the cavalry through the Amandara Pass. At about 7.30am, the cavalry squadrons came in sight of Chakdara Fort. Everything was ominously quiet. A thin column of smoke rose from the gun tower. A helio was flashed and immediately there was a heavy burst of firing from the fort, which was taken up by the surrounding tribesmen. The cavalry rode across the plain and entered the fortified entrance to the bridge, the tribesmen withdrawing swiftly up the river.

With the appearance of Adam’s squadrons, Rattray led a party out of the fort to re-capture the civilian hospital, while Captain Baker cleared the sangars above the fort, from which fire was being directed at the approaching cavalry. The siege of the fort was over.

The Malakand Relief Column at Dargai: Malakand Rising, 26th July to 22nd August 1897 on the North-West Frontier of India: drawing by Edmund Hobday

The Malakand Field Force:

The troops already in Malakand, Chakdara and Dargai were incorporated in the Malakand Field Force.

The First Brigade, commanded by Brigadier-General Meiklejohn, concentrating at Amandara, comprised 1st Royal West Kents, 24th Punjab Infantry, 31st Punjab Infantry and 45th Rattray’s Sikhs.

The Second Brigade, commanded by Brigadier-General Jeffreys, concentrating at Khar and Malakand, comprised 1st Buffs (East Kent Regiment), 35th Sikhs, 38th Dogras and the Guides Infantry.

Divisional troops comprised 1 squadron 10th Bengal Lancers, 11th Bengal Lancers, Guides Cavalry, No. 1 Mountain Battery RA, No. 7 Mountain Battery RA, No. 8 Bengal Mountain Battery, 21st Punjab Infantry, 2 companies of 22nd Punjab Infantry, No. 4 Company Bengal Sappers and Miners and No. 5 Company Madras Sappers and Miners.

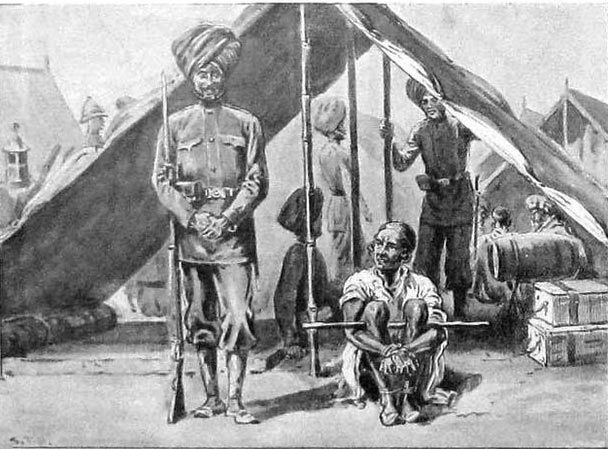

Tribesman held prisoner in Khar: Malakand Rising, 26th July to 22nd August 1897 on the North-West Frontier of India

The Third, Reserve Brigade, commanded by Brigadier-General Wodehouse, comprised 1st Queen’s Surreys, 2nd Highland Light Infantry, 6 companies of 22nd Punjab Infantry, 39th Garwhal Rifles, No. 10 Field Battery, RA and No. 3 Company Bombay Sappers and Miners.

An advanced supply depot was established at Khar, between Malakand and Chakdara. The various units making up the force were to concentrate in the Swat Valley by 8th August 1897. In the meantime, advances were made up the Swat Valley.

Sikh troops looting and destroying a village in the Swat Valley: Malakand Rising, 26th July to 22nd August 1897 on the North-West Frontier of India

Brigadier-General Jeffreys occupied a number of villages around the area of Khar, whose male inhabitants had taken part in the attack on Malakand. The villages were deserted. The troops destroyed the fortifications. On reports that Bunerwals and Hindustani fanatics were arriving in the area, the passes of Shakot, Morah and Charat were reconnoitred. Groups of tribesmen were found and dispersed by the cavalry.

The ‘Mad Fakir’ was reported to be in Mingaora, the ancient capital of the old Buddhist state of Udyana in Upper Swat.

One of the Mad Fakir’s urgings on his followers was that the garrison at Malakand was the full extent of Britain’s military force in India. The trebling of the force in a matter of days, with extensive activity in bringing up supplies and establishing bases, was troubling evidence for the tribesmen of the unreliability of this claim.

On 9th August 1897, the Ranizai and Khan Khel jirgas from Lower Swat came in to the British headquarters at Chakdara to negotiate. Terms of a fine and surrender of weapons were imposed on them and the members of these clans were permitted to return to their villages.

On 12th August 1897, the jirgas from the Khwazazai clans, based on the northern bank of the Swat River in Dir, came in to the British camp to negotiate and were given the same terms.

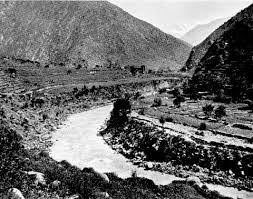

Swat River Valley at Landakai: Malakand Rising, 26th July to 22nd August 1897 on the North-West Frontier of India

The action at Landakai:

General Blood prepared to move his force into Upper Swat, the area to

the north of Landakai, known as ‘the Gate of Swat’. To cover the right

flank of the force from interference by the Bunerwals, Brigadier-General

Wodehouse moved parts of the reserve Third Brigade (the HLI, No. 3

Company Bombay Sappers and Miners and 1 squadron of the 10th Bengal Lancers) to Rustam, the south-west approach to Buner.

The main force assembled for the advance up the Swat River at Amandara and comprised Brigadier-General Meiklejohn’s First Brigade, with the cavalry, guns and Sappers and Miners of the divisional troops.

On 16th August 1897, the force moved from Amandara to the village of Thana on the Swat River, bringing twelve days supplies but no tents. The baggage was left at Thana, with a strong guard from the 35th and 45th Sikhs and the 11th Bengal Lancers.

On 17th August 1897, a squadron of the 11th Bengal Lancers, commanded by Major Beatson, moved out at 6.30am to reconnoitre the left bank of the river. A skirmish took place with tribesmen at the village of Jalala.

At this point, a ridge extended from the mountains to near the river. Jalala lay between the end of the ridge and the river. Beyond the Jalala ridge lay a nullah running down to the river and a second spur, before a ravine and the substantial Landakai ridge.

The Landakai ridge extended from the mountain line and ended abruptly at the gorge through which ran the Swat River. A narrow causeway, sufficient only for a single file, was built into the cliff above the river and ran for a mile, until the ridge ended, with an open area devoted to rice fields and the village of Landakai. The tribesmen were positioned along the crest of the ridge, in a sequence of stone sangars. The causeway had been broken down in several places.

The relief of Chakdara Fort: Malakand Rising, 26th July to 22nd August 1897 on the North-West Frontier of India: illustration from Le Petit Parisien

The cavalry found tribesmen skirmishers occupying Buddhist ruins on the spur above Jalala. 2 companies of the Royal West Kents cleared the ruins and the battalion took up positions along the Jalala Ridge. At 9am, the 10th Field Battery and No. 7 Mountain Battery came into action on Jalala Ridge, firing on the sangars along the Landakai Ridge.

Lieutenant Alexander Murray VC: Malakand Rising, 26th July to 22nd August 1897 on the North-West Frontier of India

Brigadier-General Meiklejohn took the 24th Punjab Infantry and the 45th Sikhs into the mountains and moved along, parallel with the Swat River, to take the Landakai Ridge position in flank. If this succeeded, the tribesmen would be unable to withdraw along the ridge into the mountains and be forced to retreat by descending into the rice fields at the back of the ridge, leaving themselves vulnerable to cavalry attack, provided the cavalry regiments could negotiate the river causeway.

The Royal West Kents moved across the intervening ground from Jalala and began the climb onto the Landakai Ridge.

Most of the tribesmen, seeing the threat from Meiklejohn’s force moving along the mountain line on their left, soon to cut off their retreat into the mountains and under destructive fire from the guns on the Jalala Ridge, began to retreat down from the ridge into the fields on the far side, leaving only their more determined brothers. A group of Bunerwals, distinguishable by their dark blue and grey clothing, could be seen moving away along the mountain tops, back towards the passes to Buner. This group later skirmished with the Thana baggage guard of the 11th Bengal Lancers.

Attack on 24th Punjab Infantry by the Bunerwal ghazis at Landakai on 17th August 1897: Malakand Rising, 26th July to 22nd August 1897 on the North-West Frontier of India: drawing by Edmund Hobday

As the 24th Punjabis climbed up the steep hillside to reach the tribesmen, a group of Bunerwal ghazis launched a charge down the hill, to be met with a destructive rifle fire from the 24th. The surviving ghazis were driven back onto the ridge.

By the Swat River, the Madras Sappers and Miners worked to clear the obstructions on the causeway and mend the damage, to permit the cavalry to make their way round to the rear of the Landakai Ridge position. Even when repaired, the causeway was so narrow, that the cavalrymen had to dismount and lead their horses in single file. Captain Palmer of the Guides Cavalry gathered a small force at the far end of the causeway and headed off in pursuit of the retreating tribesmen making for the hills across the rice fields.

Lieutenant Colonel Adams, Guides Cavalry: Malakand Rising, 26th July to 22nd August 1897 on the North-West Frontier of India

Most of the tribesmen were now in the foot hills above the village of Nawakila, 1 ¼ miles to the east of Landakai. Lieutenant-Colonel Adams directed the sowars to head for a clump of trees from which dismounted fire could be directed at the tribesmen.

Captain Palmer was riding with Lieutenant Greaves, an officer of the Lancashire Fusiliers, with the force as correspondent for the Times. Ignoring, or not hearing Adams’ order, these two officers continued in direct pursuit, outstripping the accompanying sowars. As they came up with the tribesmen, a number turned on the two officers. Both were shot. Palmer was rescued by 2 sowars of the Guides. Greaves’ horse carried him into the middle of the tribesmen, where he fell to the ground. A party comprising Colonel Adams, Lieutenant Viscount Fincastle, who was also acting as a news correspondent, Lieutenant Maclean of the Guides and a number of sowars came up to rescue Greaves. In the resulting melee Greaves was dragged onto a horse, but again shot, this time fatally and Maclean was mortally wounded. The party managed to escape to the small wood, under covering fire from the remaining sowars.

For this incident, Adams and Fincastle received the Victoria Cross and Jemadar Bahadur Singh and 4 men of the Guides Cavalry received the Indian Order of Merit. Lieutenant Maclean was awarded a posthumous VC.

The rescue of Palmer and Greaves by Colonel Adams and Viscount Fincastle, who both won the VC: Malakand Rising, 26th July to 22nd August 1897 on the North-West Frontier of India

The infantry regiments descended from the Landakai Ridge and crossed the fields into the foothills, by which time the tribesmen were well into the mountains.

Lieutenant-Colonel Adams assembled the 2 cavalry regiments and continued up the valley towards Barikot. They came up with a force of around 150 tribesmen holding the village of Abuwa. The cavalry drove them out and then returned to camp at Landakai.

Around 1,500 of the tribesmen who had retreated towards the Morah Pass attempted an attack on the baggage at Thana but were driven off. These were the Bunerwals seen earlier to be moving along the mountain crest.

The camp at Thana: Malakand Rising, 26th July to 22nd August 1897 on the North-West Frontier of India

British casualties in the day were the 2 British officers killed and 2 officers and 7 men wounded. The losses of the tribesmen were estimated at more than 300.

Further operations in the Malakand Rising:

On 18th August 1897, the Malakand Field Force continued its

march up the east bank of the Swat River, reaching the village of

Ghalegai. All the villages on the route were abandoned. The villagers

at Ghalegai were still in place and complied with the requirements

imposed upon them, surrendering all arms and British looted property and

providing supplies and transport. When a few shots were fired into the

British camp, the villagers drove the offenders away.

On the next day, the column marched to Mingaora, where it remained until 24th August 1897, while the political officer, Major Deane, negotiated terms. On 22nd August 1897, the jirgas of the Upper Swatis agreed to the terms required of them, surrender of firearms and payment of fines.

The Mian Guls withdrew to Buner, as did the Mad Fakir, beyond the present reach of the British. A substantial number of firearms was collected from the now compliant tribesmen of the area, with grain, fodder and fuel for the use of the troops and some transport animals. Reconnaissance parties moved about the country, as far as the Kotkai Pass in the east, on the border of Bunerwal country, conducting surveying work.

Villagers were required to demolish the fortifications in their houses and villages. A postal service was established between Thana and Mingaora, for the temporary purposes of the British troops, which the tribes were required to protect.

On 22nd August 1897, the jirgas of the Upper Swat signed a document of unconditional surrender. As part of the terms, the assurance was given on behalf of the British Government in India that there was no intention to interfere with the tribes or their country, but that ‘peace must be maintained on the Border’.

Major Deane questioned widely as to why the uprising had taken place. There seemed to be no particular complaint about the conduct of the British. The only motivation seemed to be religious fanaticism, fanned by the ‘Mad Fakir’ and other mullahs.

British gunners with a 12 pounder field gun: Malakand Rising, 26th July to 22nd August 1897 on the North-West Frontier of India

The move towards Buner:

On 24th August 1897, the Malakand Field Force returned to Barikot and, on 26th

August 1897, to Khar and then Malakand. The intention was to invade

Bunerwal country and complete the operations against the tribes involved

in the attack on Malakand.

By this time the British Indian Army was dealing with the uprisings by the Mohmands, immediately to the west of the area of operations of the Malakand Field Force and the uprising in the Tirah, to the south of the Kabul River. The Government of India decided that the invasion of Buner should be left for the moment and that General Blood’s force should move west, to assist General Elles in dealing with the Mohmands, in the area around the Nawagai Valley.

The operations in the Swat Valley ended and the political officers were left to monitor compliance with the cease fire agreements. A substantial force remained in the area to support the Khan of Dir, in ensuring compliance by the villages in his area.

Casualties in the Malakand Rising: These are set out in the narrative above.

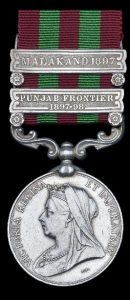

Indian General Service Medal 1854-1895 with the clasps ‘Malakand 1897’ and ‘Punjab Border 1897-1898’

Battle Honour and decorations for the Malakand Rising:

The battle honour ‘Malakand’ was awarded to those regiments that took part in the defence of Malakand and Chakdara: 11th Bengal Lancers, the Guides, 24th Punjab Infantry, 31st Punjab Infantry, 35th Sikhs and 38t Dogras.

The battle honour ‘Punjab Frontier’ was awarded to the regiments that took part in the Malakand Field Force, along with the regiments involved in the Tochi and Mohmand operations.

All troops and civilian staff, who either took part in the defence of Malakand and Chakdara or took part in the operations beyond Jalala, received the Indian General Service Medal 1895, silver for troops and bronze for civilians, with the clasp ‘Punjab Frontier 1897-8’. For the garrisons of Malakand and Chakdara and the troops and supporters of the relief force, the additional clasp was issued ‘Malakand, 1897’. Where an individual already had the medal, he added the appropriate clasps to his existing medal.

Lieutenant Edmund Costello VC: Malakand Rising, 26th July to 22nd August 1897 on the North-West Frontier of India

Brigadier-General Meiklejohn was made Commander of the Bath (CB). Captain Wright and Lieutenants Climo and Rattray were awarded the DSO. Lieutenant-Colonel Adams, Lieutenant Viscount Fincastle and Lieutenant Maclean received the Victoria Cross for the incident at Landakai on 17th August 1897. Lieutenant Costello received the Victoria Cross for rescuing the havildar on 26th July 1897.

Several Indian sepoys and sowars received the Indian Order of Merit, including the defenders of the Serai at Malakand, the Signal Tower at Chakdara and the sowars who rode to the rescue of the 2 officers at Landakai with Adams, Maclean and Fincastle and the sepoys who assisted Lieutenant Costello in rescuing the havildar.

Follow-up to the Malakand Rising:

See the entry for ‘Mohmands 1897’ and ‘Buner 1898’ for the subsequent operations of the Malakand Field Force.

Anecdotes and traditions from the Malakand Rising:

- A striking feature of warfare on the North-West Frontier was the responsibility that fell on junior British officers, a consequence of the small establishment for British officers in Indian Army regiments. Lieutenant Climo, aged 29, took command of his regiment, the 24th Punjab Infantry, on the second day of the assault on the Malakand, conducting himself with resource and determination, thereby winning a DSO. When the order for the Guides to march for the Malakand arrived at Mardan, on 26th July 1897, the only British officer in camp was Lieutenant Elliot-Lockhart, who immediately put the regiment’s cavalry and infantry, effectively 2 regiments, in motion. The garrison at Chakdara was commanded by Lieutenant Rattray, until the arrival of Captain Wright of 11th Bengal Lancers, who left the day to day conduct of the defence to Rattray.

- ‘Resource and determination’ are qualities that must be attributed to many of the soldiers of the Malakand and Chakdara garrisons, particularly Colonel Meiklejohn, Lieutenant-Colonel McRae of the 45th Sikhs, Captain Wright of the 11th Bengal Lancers, Subadar Syed Ahmed Shah and his 31st Punjabis in the Serai and Lance Naik Vir Singh and his 45th Sikhs in the Signal Tower, to name but a few.

- The 12 pounder BL (breech loading) field gun was used for the first time in Indian frontier warfare by the Royal Artillery. These guns were present in the Chitral Relief Force but were not used in action.

- The Chakdara Signal Tower is now called ‘Churchill’s picket’. It is not clear why this should be. Winston Churchill joined the Malakand Field Force after the fighting in the Swat Valley, when General Blood was about to move west against the Mohmands in the Nawagai Valley. No doubt, Churchill visited Chakdara and the Signal Tower, but he will not have seen action in that area. Any dispatch he sent from Chakdara will have been by telegraph from the fort, rather than by heliograph from the Signal Tower.

- Lieutenant Colonel Lamb, the commandant of the 24th Punjab Infantry, received a bullet wound in the leg, during the first attack on the Malakand, on 26th July 1897. Amputation of the leg was delayed, while a Röntgen X-ray machine was brought up from India, to see if the bullet could be located and removed. When the machine arrived, it was found to be damaged and unusable. Colonel Lamb’s leg was amputated, but the delay proved fatal and Colonel Lamb died.

- During his investigation of the reasons for the uprising, the political officer in Malakand, Major Deane, asked tribal leaders why the Malakand Camp had been attacked. He received the answer that the British had not issued any order forbidding an attack.

- ‘The McMunn Book’: A leading Indian Army officer wrote short comments for each of those regiments illustrated in his copy of McMunn’s ‘The Armies of India’: His comments for regiments involved in the Malakand campaign were (not all the regiments involved appear in the book): Guides: ‘God’s Own Very Good’: 3rd Company Sappers and Miners: ‘Fair’: 22nd Punjab Infantry: ‘Very good honest reliable battalion’: 24th Punjab Infantry: ‘A1’: 31st Punjab Infantry: ‘Very good’: 38th Dogras: ‘Very good’: 39th Garwhalis: ‘Excellent’: 45th Sikhs: ‘Very good’.

- Most of the regiments involved in the operation comprised Sikhs, Pathans, Punjabi Mussulmans and Dogras. The 3rd and 4th Companies of Sappers and Miners were from Bombay and will have been Hindu and Muslim, as will the 5th Company from Madras.

- The Guides were formed from a wide range of nationalities, including Pathans of several tribes, Afghans, Sikhs, Dogras, Muslim and Hindu Punjabis, Turkmens, Gurkhas, Persians and others.

- Officers in the Sappers and Miners were from the Royal Engineers. Officers in the Mountain Batteries were from the Royal Artillery. These two corps made a substantial contribution to the Indian Army. General Sir Bindon Blood was a Royal Engineer.

- Brigadier-General Meiklejohn’s daughter Meg aged 4 was in the camp at Malakand with her nurse, when the attack took place on 26th July 1897.

- Comment is made on the conduct of the Guides Cavalry and the 11th Bengal Lancers in the authoritative work, ‘Small Wars’, by Colonel Callwell, Third Edition 1908. Callwell states “It is, however, only right to point out that the mounted troops which performed such signal service during the advance towards Chitral and during the operations of the Malakand field force, enjoyed the advantage of great experience in irregular warfare. Because regiments like the Guides and the 11th Bengal Lancers were able to play an important tactical rôle in theatres of war so awkward to traverse by mounted men as Swat and Bajaur, it does not follow that corps trained on more favourable ground and accustomed only to ordinary cavalry manoeuvres, would do as well under the same conditions.”

- Several Indian Army regiments maintained in their informal titles references to the British officers who had raised them. The Guides were ‘Lumdsen’s’. The 11th Bengal Lancers were ‘Probyn’s Horse’. The 45th Sikhs were ‘Rattray’s Sikhs’.

Winston Churchill as a 19 year old officer of the 4th Hussars: Malakand Rising, 26th July to 22nd August 1897 on the North-West Frontier of India

References for the Malakand Rising:

Frontier and Overseas Expeditions from India Volume 1 published by the Government of India

North West Frontier by Captain H.L. Nevill DSO, RFA

Malakand Field Force by Winston Churchill

The North-West Frontier by Michael Barthorp

The Frontier Ablaze, the North-West Frontier Rising 1897-1898 by Michael Barthorp

The History of Probyn’s Horse (11th and 12th Bengal Lancers)

Sketches on service during the Indian Frontier Campaigns of 1897 by Edmund Hobday

The previous battle of the North-West Frontier of India is the Siege and Relief of Chitral

The next battle in the British Battles sequence is the Malakand Field Force 1897

No comments:

Post a Comment